Dead and Going to Die

We photograph things in order to drive them out of our minds.

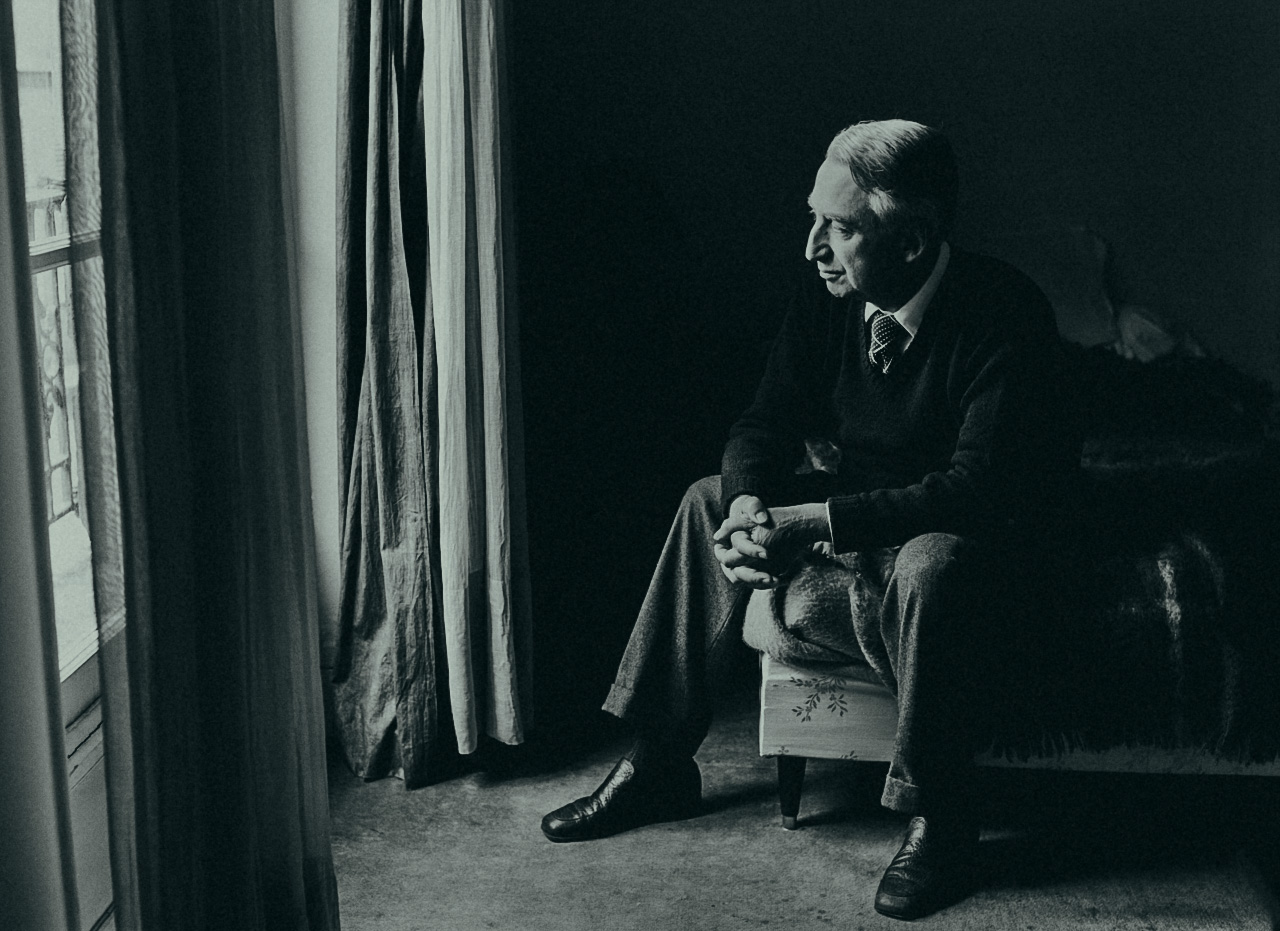

On Monday 25 February 1980, Roland Barthes attended a lunch hosted by François Mitterrand. It may well have been exasperation or boredom (for he was often bored) that made him decide, when the lunch concluded, to clear his head and walk home alone to his apartment on the rue Servandoni. At about 3.45pm, Barthes paused before crossing the street at 44 rue des Écoles; he looked left and right, but failed to spot an advancing laundry van, which knocked him down. Unconscious and bleeding from the nose, without his identity card or any other form of identification, he was taken to the Salpêtrière hospital by ambulance. No one knew who he was, which is why the media did not get hold of the news much later. He died next month.

Yesterday I read Camera Lucida (Roland Barthes, La Chambre Claire, 1980) again. A book of mourning, a book of photography. What Barthes had written was neither a work of theoretical strictness nor avant-garde polemic, still less a history or sociology of photography. Instead, it was frankly personal, even sentimental collection of notes, perhaps something to be expanded upon, but left in its raw form and immortalized as such. And it can change somebody’s life. He wrote this book to figure out for himself if photography had an essence.

The most interesting part of the book is Barthes’ framework for viewing photos through studium and punctum. Studium denotes the cultural, linguistic, and political interpretation of a photograph; punctum denotes the wounding, personally touching detail which establishes a direct relationship with the object or person within a photograph. Written after his mother’s death, Camera Lucida is as much a reflection on death as it is on photography. Death and photography co-mingle in a way no other art does. “The Photograph does not call up the past (nothing Proustian in a photograph),” writes Barthes. “The effect it produces upon me is not to restore what has been abolished (by time, by distance) but to attest that what I see has indeed existed.”

Instead of relying mostly on outward theory, he went looking for a photograph of his mother after she died. He went through photographs of his mother, throughout her life, not finding her, but he finally came upon a photograph taken in 1898 when she was five years old.

“There I was, alone in the apartment where she had died, looking at these pictures of my mother, one by one, under the lamp, gradually moving back in time with her, looking for the truth of the face I had loved. And I found it. The photograph was very old. The corners were blunted from having been pasted into an album, the sepia print had faded, and the picture just managed to show two children standing together at the end of a little wooden bridge in a glassed in conservatory, what was called a Winter Garden in those days. My mother was five at the time (I898), her brother seven. He was leaning against the bridge railing, along which he had extended one arm; she, shorter than he, was standing a little back, facing the camera; you could tell that the photographer had said, ‘Step forward a little so we can see you’; she was holding one finger in the other hand, as children often do, in an awkward gesture. The brother and sister, united, as I knew, by the discord of their parents, who were soon to divorce, had posed side by side, alone, under the palms of the Winter Garden (it was the house where my mother was born, in Chennevieres-sur-Marne).

I studied the little girl and at last rediscovered my mother. The distinctness of her face, the naive attitude of her hands, the place she had docilely taken without either showing or hiding herself, and finally her expression, which distinguished her, like Good from Evil, from the hysterical little girl, from the simpering doll who plays at being a grownup-all this constituted the figure of a sovereigninnocence (if you will take this word according to its etymology, which is: ‘I do no harm’), all this had transformed the photographic pose into that untenable paradox which she had nonetheless maintained all her life: the assertion of a gentleness. In this little girl’s image I saw the kindness which had formed her being immediately and forever, without her having inherited it from anyone; how could this kindness have proceeded from the imperfect parents who had loved her so badly-in short: from a family? Her kindness was specifically out-if-play, it belonged to no system, or at least it was located at the limits of a morality (evangelical, for instance); I could not define it better than by this feature (among others): that during the whole of our life together, she never made a single ‘observation.’ This extreme and particular circumstance, so abstract in relation to an image, was nonetheless present in the face revealed in the photograph I had just discovered. ‘Not a just image, just an image,’ Godard says. But my grief wanted a just image, an image which would be both justice and accuracy-justesse: just an image, but a just image. Such, for me, was the Winter Garden Photograph.”

Therein lies its haunting, disturbing quality: photography attests to our mortality. “The photograph possesses an evidential force, and that its testimony bears not on the object, but on time. From a phenomenological viewpoint, in the Photograph, the power of authentication exceeds the power of representation.” Whereas film presents the flow of continuous time—the absence of the past, in effect—a photograph breaks our notions of continuity. So the punctum “is Time, the lacerating emphasis of the noeme (“that-has-been”), its pure representation.”

I am older than my mother ever got to be.

Since she’s died at the age of 39, or, perhaps, precisely because she has died, I have gained a greater sense of self and became more of the person I always wanted to be but was too scared to try. And as I move further away from that uncertain sixteen-year-old who stoicly buried his mother, I can’t help but feel that I am losing her all over again.

Searching for her face and loooking back to the days of my conception around these days of august 1970, I have found this old 8mm movie taken by my father at the time when my mom was pregnant with me. Only four sharp frames remained. She saw something in the distance, stood quietly and thoughtfully for a moment and then suddenly she frowned and turned her head with eyes closed. Going back to the house she fell down the stairs and cut her knee. That memory remained as a birth scar exactly 8mm long on my own right knee and as a habit of scratching it when I am nervous. But the memory of what we saw is lost forever.

The desire to get to know my mother’s face again may spring from a realization of how much I am like her. How often do I catch a glimpse of my own reflection in the mirror, surprised to discover my mother’s expressions in my own?

And what could my mother say to me now, to this person she never met?

Reconstruction of my mother’s face based on some small 3cm ID photo taken at the time when she was pregnant with me.

At the end of her life, shortly before the moment when I looked through her pictures and discovered the Winter Garden Photograph, my mother was weak, very weak. I lived in her weakness (it was impossible for me to participate in a world of strength, to go out in the evenings; all social life appalled me.) During her illness, I nursed her, held the bowl of tea she liked because it was easier to drink from than from a cup; she had become my little girl, uniting for me with that essential child she was in her first photograph.

Roland Barthes